-

Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story (2024) Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

I am Not a Number (2019) by Jenny Kay Dupuis and Kathy Kacer

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

Muinji’j Asks Why (2022) by Shanika MacEachern and Breighlynn MacEachern

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

Not My Girl (2014) by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

Red Bird Sings: The story of Zitkala-Ša (2011) by Gina Capaldi

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

Secret Pocket (2023) by Peggy Janicki

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

Shin-chi’s Canoe (2008) by Nicola Campbell

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

When We Are Alone (2016) by David A. Robertson

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

-

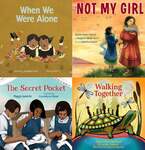

Stolen Childhood: Picture Book Stories of Indian Residential Schools

Maughn Rollins Gregory

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries American and Canadian government agencies and Christian churches established Indian residential schools where hundreds of thousands of children were “reeducated” in English and Christianity. They were not allowed to use their native languages or given names, to practice their religions, or to communicate with their siblings or parents. They were made to work in crop fields, kitchens, laundries, and industrial workshops. Many were physically and sexually abused. Many never saw their families again. The nine picture books reviewed here are accounts of survivors of residential schools from eight different Indigenous nations. In addition to depicting the violence attending these schools, the books show the courage and intelligent resilience of the resident children—inventing sign language to secretly communicate with each other, stealing food, and attempting escape. These books can help Indigenous families and descendants of settler colonizers explore this part of history in ways that may be uncomfortable but that will generate the kind of understanding of the past that can inform taking responsibility for the present and the future.

Printing is not supported at the primary Gallery Thumbnail page. Please first navigate to a specific Image before printing.