"To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul."

Simone Weil, The Need for Roots, 1949

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza are only the most recent events that make young people experience, witness, and otherwise learn about the ways that lives are uprooted – by war and other forms of violence, and also by every kind of involuntary and unplanned exile – internment, forced immigration, natural disasters. Simone Weil’s classic work The Need for Roots explores these multiple kinds of damage and asks important questions about how healing can happen. Her work inspires this thematic chapter of Thinking in Stories.

Philosophy for children has traditionally raised questions within a framework of safety: the classroom and the world of children’s stories are usually secure places within which disturbing questions can arise. However, in recent decades, educators have addressed young people living in situations of war and displacement, suggesting ways to understand and cope with dislocation and confusion.

Philosophy for children has traditionally raised questions within a framework of safety: the classroom and the world of children’s stories are usually secure places within which disturbing questions can arise. However, in recent decades, educators have addressed young people living in situations of war and displacement, suggesting ways to understand and cope with dislocation and confusion.

Some of the books profiled in these reviews suggest indirect ways of talking about war and displacement. One reflects on the oddity of the idea of an enemy, and how ordinary people can suddenly become enemies. Another notices the change in the kinds of friendship we value in different circumstances. Yet another asks how people can keep on with the basic progress of life under hostile circumstances. Another book reflects on how the concept of “here” becomes a problem for people who are always moving, who must establish a new base each day. The reviews point to a rich literature; there are likely other promising books to add to this collection.

Some reviews suggest new uses for old books. In the classic picture book, The Noisy Book (1939) by Margaret Wise Brown, a dog who is being shipped in a crate learns to distinguish sounds, partly putting aside his frustration at not being able to see. This story, with echoes of stoic philosophers, is designed to talk children through hard times, to provide a way out for them, and could be helpful with the many frustrations of refugee life. (It’s available, like many good older books, on The Open Library.)

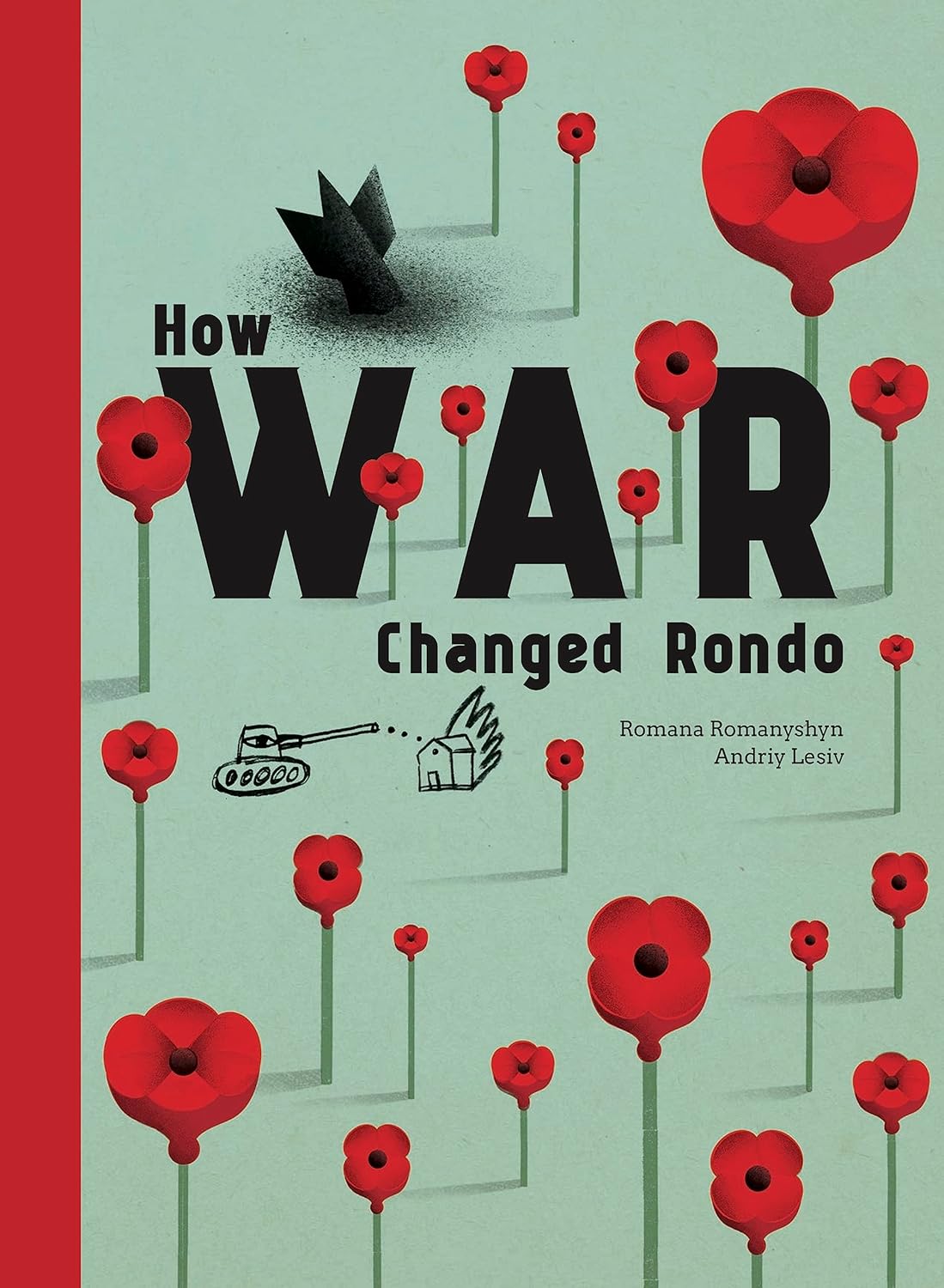

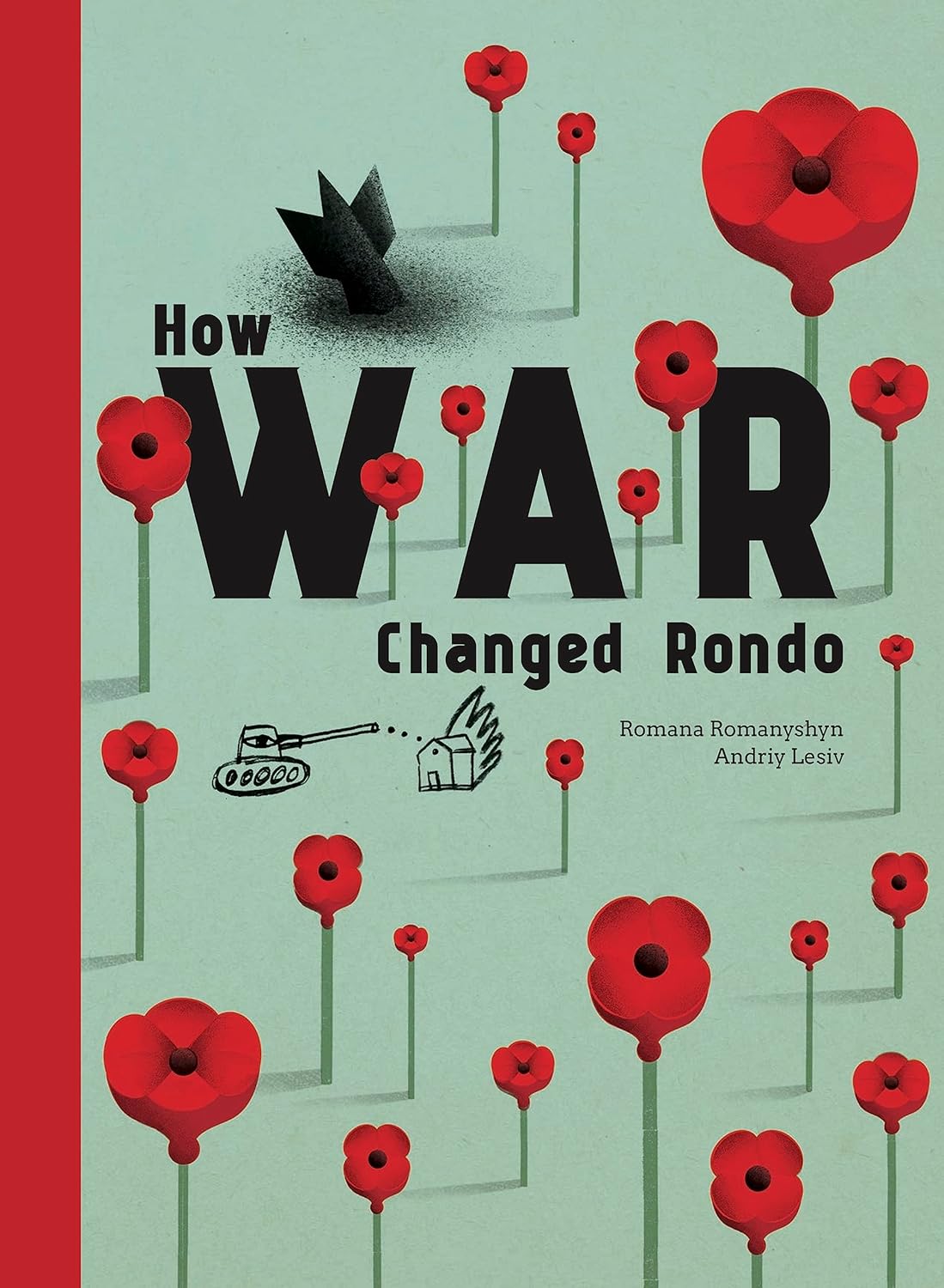

Maughn Gregory’s review of How War Changed Rondo (2021) raises important questions about our list, and the limits of this project. This book presents a powerful myth of war, and it recommends responses and ways of thinking. How War Changed Rondo may be most helpful just as myth, as a way of making sense of intolerable events. It can also be used as a text to promote thinking, if one questions the assumptions that underlie the myth and the images.

Gregory’s review shows how a teacher might lead such a discussion – at what points the author’s and illustrator’s model is open to question. But a teacher might also choose not to use the book in this way, responding to the needs of a particular group of children. Philosophical investigation is one important way of working with children, and it seems appropriate even in terrible situations to think things through, but no sane person would insist on this as the only way of helping traumatized children. Sometimes, myths may need to be left simply as myths – as stories that give some meaning to a difficult sequence of events. The teacher must decide which approach a particular group of children need, what they are ready for.

Gregory’s review shows how a teacher might lead such a discussion – at what points the author’s and illustrator’s model is open to question. But a teacher might also choose not to use the book in this way, responding to the needs of a particular group of children. Philosophical investigation is one important way of working with children, and it seems appropriate even in terrible situations to think things through, but no sane person would insist on this as the only way of helping traumatized children. Sometimes, myths may need to be left simply as myths – as stories that give some meaning to a difficult sequence of events. The teacher must decide which approach a particular group of children need, what they are ready for.

Matthew Lipman’s words from the interview in Socrates for Six-Year-Olds (BBC 1990) express one kind of support these materials can provide. Lipman is not solving children’s problems or telling them how to feel. He reminds them of the power they always already have:

Children don’t have much private property. Perhaps they own their clothes and a few toys. It’s hard to say that they own even their bed or the furniture in their rooms that belong to the family or the parents. And so, the kind of security that comes with the ownership of property is usually not permitted to children. On the other hand, they do have their thoughts and they cherish these. They are proud of these. These are very consoling. They are what [children] can be secretive about and no one else can invade this privacy. And they have the use of language, which gives them a great deal of power; because with words they can talk to one another and communicate with one another, but also they can defend themselves. I think words mean power to children, and having thoughts is a source of richness—perhaps the only source of richness.

Philosophy may have only a small part to play in comforting and strengthening children in extreme distress, and in helping children who are aware of, but not directly involved in those situations learn about them, ask questions about them, and think about them carefully. Other kinds of engagement may be more needed. We just can’t know, in advance, what conversations will be helpful. If there is a way that the community of inquiry approach can be of service here, we should explore that.

Philosophy may have only a small part to play in comforting and strengthening children in extreme distress, and in helping children who are aware of, but not directly involved in those situations learn about them, ask questions about them, and think about them carefully. Other kinds of engagement may be more needed. We just can’t know, in advance, what conversations will be helpful. If there is a way that the community of inquiry approach can be of service here, we should explore that.

Simone Weil, The Need for Roots, 1949

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza are only the most recent events that make young people experience, witness, and otherwise learn about the ways that lives are uprooted – by war and other forms of violence, and also by every kind of involuntary and unplanned exile – internment, forced immigration, natural disasters. Simone Weil’s classic work The Need for Roots explores these multiple kinds of damage and asks important questions about how healing can happen. Her work inspires this thematic chapter of Thinking in Stories.

Some of the books profiled in these reviews suggest indirect ways of talking about war and displacement. One reflects on the oddity of the idea of an enemy, and how ordinary people can suddenly become enemies. Another notices the change in the kinds of friendship we value in different circumstances. Yet another asks how people can keep on with the basic progress of life under hostile circumstances. Another book reflects on how the concept of “here” becomes a problem for people who are always moving, who must establish a new base each day. The reviews point to a rich literature; there are likely other promising books to add to this collection.

Some reviews suggest new uses for old books. In the classic picture book, The Noisy Book (1939) by Margaret Wise Brown, a dog who is being shipped in a crate learns to distinguish sounds, partly putting aside his frustration at not being able to see. This story, with echoes of stoic philosophers, is designed to talk children through hard times, to provide a way out for them, and could be helpful with the many frustrations of refugee life. (It’s available, like many good older books, on The Open Library.)

Maughn Gregory’s review of How War Changed Rondo (2021) raises important questions about our list, and the limits of this project. This book presents a powerful myth of war, and it recommends responses and ways of thinking. How War Changed Rondo may be most helpful just as myth, as a way of making sense of intolerable events. It can also be used as a text to promote thinking, if one questions the assumptions that underlie the myth and the images.

Matthew Lipman’s words from the interview in Socrates for Six-Year-Olds (BBC 1990) express one kind of support these materials can provide. Lipman is not solving children’s problems or telling them how to feel. He reminds them of the power they always already have:

Children don’t have much private property. Perhaps they own their clothes and a few toys. It’s hard to say that they own even their bed or the furniture in their rooms that belong to the family or the parents. And so, the kind of security that comes with the ownership of property is usually not permitted to children. On the other hand, they do have their thoughts and they cherish these. They are proud of these. These are very consoling. They are what [children] can be secretive about and no one else can invade this privacy. And they have the use of language, which gives them a great deal of power; because with words they can talk to one another and communicate with one another, but also they can defend themselves. I think words mean power to children, and having thoughts is a source of richness—perhaps the only source of richness.

Browse the Thinking in Stories about War and Dispossession Collections:

1. Children’s Experiences of War

2. Children’s Experiences of Forced Migration and Deportation

3. Children’s Experiences of Internment

4. Children’s Experiences of Displacement by Natural Disaster (flood, fire, famine)